Water is the life blood of every community. The man who did more than any other to furnish that vital element to Los Angeles is William Mulholland, who for many years was chief engineer and general manager of the city-owned Bureau of Water Works and Supply (now the Water System of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power). He died in 1935 but his work lives on. Every time a faucet is turned the water it releases is a reminder of the man whose life was devoted to public service.

Los Angeles is no longer a one-horse town but it is a one-river town – or, at least, it used to be. That river is the Los Angeles River. Spanish explorers discovered it in 1769 and with prophetic vision said that the area surrounding it “has all the requisites for a large settlement.” That judgment was rendered seven years before the Declaration of Independence was signed. From the humble pueblo that was founded in 1781, it has grown into the second largest city in the United States.

The vision that prompted the Spanish explorers to designate this location as one of promise was carried to fruition by the resourcefulness of the pioneers who followed. High on the list of these stalwarts is William Mulholland. He is best known for building the Los Angeles Owens River Aqueduct; a man-made river flowing through steel pipes and concrete conduits that would far surpass the capacity of the local “river.” Within the 20th century, Los Angeles has grown from a town of 100,000 population to a city of more than 3,000,000. In the same time, its water supply has progressed from a small system which included open ditches to one of the largest city water supply systems in the nation.

The courses of Los Angeles, the city, and William Mulholland, the man, were singularly parallel. Each had a modest beginning.From a small group of intrepid settlers the pueblo passed through various stages of development, making its own way against almost every conceivable obstacle to become the international city of today. It was in those early pioneer days that William Mulholland,>youthful, vibrant with life and eager for work, became a humble ditch tender. From books borrowed, or those purchased with part of his meager income, he garnered knowledge. His native intellectual ability, augmented by intensive study, began to be recognized. By his own efforts he passed from ditch tender to straw boss, to foreman, to superintendent.

Eventually, he became a figure of international fame in the fields of engineering and community building.

It was 1877 when William Mulholland rode into Los Angeles on horseback after an exciting trip through the San Joaquin valley from San Francisco. Years later he wrote: “Los Angeles was a place after my own heart. The people were hospitable … The country had the same attraction for me that it had for the Indians who originally chose this spot as their place to live. The Los Angeles River was a beautiful, limpid little stream, with willows on its banks … It was so attractive to me that it at once became something about which my whole scheme of life was woven, I loved it so much.”

It was 1877 when William Mulholland rode into Los Angeles on horseback after an exciting trip through the San Joaquin valley from San Francisco. Years later he wrote: “Los Angeles was a place after my own heart. The people were hospitable … The country had the same attraction for me that it had for the Indians who originally chose this spot as their place to live. The Los Angeles River was a beautiful, limpid little stream, with willows on its banks … It was so attractive to me that it at once became something about which my whole scheme of life was woven, I loved it so much.”

Proof of his devotion is indelibly written in his lifetime of service to the water needs of his adopted city. At the start of his career,one of the principal water ditches picked up the flow of the Los Angeles River at a point opposite Griffith Park and carried water to a reservoir in Elysian Park. Young Mulholland’s job was to keep this open water carrier in as good condition as possible. While performing this duty, and until 1881, he lived in an old house at the corner of what is now one of the city’s most beautiful intersections – Los Feliz Boulevard and Riverside Drive, a major entrance to Griffith Park. After doing his day’s work he would study textbooks on mathematics, hydraulics, geology and other subjects that he later put to practical use. For recreation he read the classics of literature and from his amazing memory could quote freely from the world’s greatest authors.

He was later to marry and have five children.

Perhaps most notably, he was the first American engineer to utilize hydraulic sluicing to build a dam. That dam was built at Silver Lake Reservoir in 1906 and served for almost 70 years. It was a new construction idea that attracted nationwide attention. Government engineers adopted the method in building Gatun Dam in the Panama Canal Zone.

His crowning achievement was the great aqueduct that stretches 238 miles from the Owens River to Los Angeles, serving people, business and industry with water that springs from the icy streams and crystal lakes fed by the snows of the lofty Eastern Sierras.

Under his leadership, an army of 5,000 men labored for five years. He successfully completed, within the original time and cost estimates, the most difficult engineering project undertaken by any American up to that time. The first aqueduct water was presented to the people of Los Angeles on November 5, 1913. In a spectacular civic ceremony at the north end of the San Fernando Valley where the aqueduct terminates, William Mulholland said with characteristic brevity and lack of ostentatiousness: “There it is: take it.” And that is exactly what Los Angeles citizens have done.

Without the additional water supply delivered by the aqueduct he built, Los Angeles could never have grown beyond the 500,000 population mark. That was the maximum number local supply sources could support. And in periods of lower rainfall, which can occur in cycles, the use of water would have had to be rigidly restricted to avert disastrous consequences.

Fortunately this possibility was reduced with the arrival of Eastern Sierra water. In 1940, the extension of the aqueduct system to tap the water of the Mono Basin was completed. In 1941, the first water from the newly completed Colorado River Aqueduct was delivered to Los Angeles to meet the water needs of the growing city. William Mulholland had boundless confidence in the destiny of Los Angeles and its neighboring communities. This faith was corroborated by the skyrocketing growth of the area in the decade following completion of the aqueduct from the Owens Valley. By 1923, the influx of population from all parts of the nation had exceeded even the most optimistic earlier estimates.

Foreseeing the need for yet another water supply source, the veteran Mulholland, then 68 years of age, personally initiated the Department of Water and Power’s six-year survey of 50,000 square miles of desert that resulted in the route ultimately selected for the Colorado River Aqueduct. This great project, in which Los Angeles and 12 other Southern California cities united to form the Metropolitan Water District, now serves more than 130 communities in six Southern California counties. William Mulholland did not live to see his greatest dream materialize. Other hands took up the work of that master builder and planner.

Yet, generations unborn will have occasion to give thanks for his engineering skill and broad foresight. What manner of man was this who in 50 years of meritorious service to the citizens of Los Angeles achieved a distinction unprecedented in the history of water development and water works construction? He was born in Belfast, Ireland, on September 11, 1855, where he attended school until he was 15 years old. Then, with the insatiable search for knowledge and experience that motivated him throughout his life, he left home to see the world. He sailed the seas as an apprentice for several years, then worked on the Great Lakes and in the lumber camps of Michigan until 1876, when he went to live with his uncle who owned a dry goods store in Pittsburgh. It was there that he read Nordhoff’s “History of California,” which fired him with an ambition to see the wonderland.

Because of his love of the sea, he decided to make the long voyage by ship. To save the $25 in gold that was charged for railroad transportation across the isthmus of Panama, he chose to walk the 47 mile distance from Colon to Balboa. This was an indication, perhaps, of the ingrained sense of thrift and values that enabled him later to complete the biggest aqueduct job of its time for less than the amount of money that the people of Los Angeles had authorized to be spent for the project.

He worked his passage as a member of the crew on a ship bound for San Francisco and sailed through the Golden Gate in February 1877. Shortly thereafter he was headed on horseback for the city of his adoption – Los Angeles – and for a destiny such as befalls few men.

Only the highlights of his accomplishments have been described. A volume could be filled with accounts of his engineering and construction achievements; another with anecdotes showing his good humor and friendliness for his fellow man; another to list his proficiency in the arts and sciences. Impressive as this may sound, it is the story of a man who rubbed shoulders with sailors and laborers and never lost the common touch while rising to the top of his profession.

His remarkable character is summed up in a tribute from one of his associates in the engineering profession, who described him in these words:

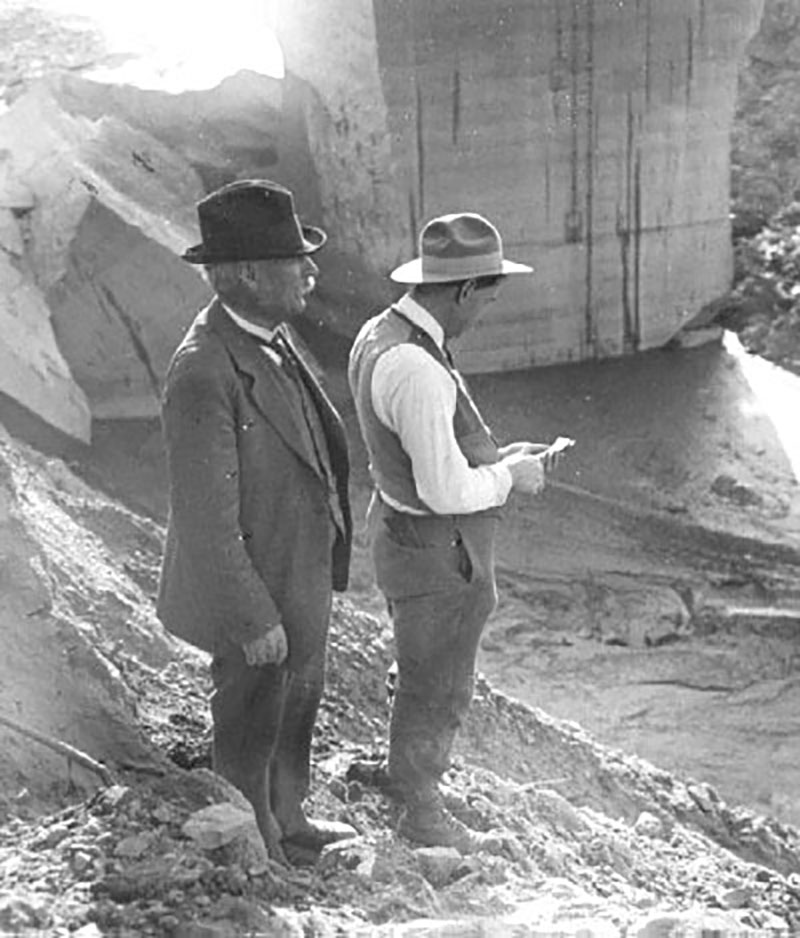

” A man with a mind remarkable for its breadth and brilliant wit. A man who can build an aqueduct, and man who can also, beside a mountain campfire, while he broils his trout, discourse on profound structural geology.

A man whose life has been spent in public service for the benefit of the masses in the land of his adoption. Remarkable for his originality of thought and analysis, yet equally active in the practical application of these ideals. Original in the minute details of construction, yet brave to the limit of conceiving and assuming the responsibilities of the greatest projects.

Kind, generous and true to the public welfare, he stands an example of what the applied scientist can do for his state when he holds his brief for the people.”