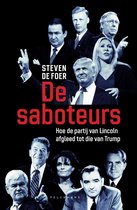

De saboteurs. Hoe de partij van Lincoln afgleed tot die van Trump door Steven de Foer. 345 pag’s. Pelckmans. 27 Euro.

Mensen lezen niet graag boeken over politici die ze haten, zei Charles Groenhuijsen me eens, ter verklaring waarom een boek over Donald Trump niet zo goed verkocht als hij had gehoopt. Als beroepslezer kan ik dat niet zo beoordelen. Ik heb meer over Trump en Wilders moeten lezen dan ik graag zou willen. Soms waren het verhelderende boeken. Een van de beste boeken die over de teloorgang van de Republikeinse Partij heb gelezen was The Destructionists. The Twenty-Five Year Crack-Up of the Republican Party door de buitengewoon goed ingevoerde en uitstekend analyserende journalist van de Washington Post, Dana Milbank.

Mijn collega Steven de Foer, correspondent in de VS voor de Standaard, publiceerde dit voorjaar De Saboteurs. Hoe de partij van Lincoln afgleed tot die van Trump. Gegeven de titel van Milbanks boek een wat ongelukkige greep, zou ik zeggen. Maar het gaat om de inhoud. En ik ben het met De Foer eens dat de teloorgang van de Republikeinen al eerder begon dan met het bommenwerpen van Gingrich, waar Milbank zijn verhaal begint.

De Foer gaat me echter te ver terug met Charles Lindbergh en Joseph McCarthy. En Barry Goldwater was een vreemd libertariër avant la lettre (en een segregatie voorstander) die in 1964 de Republikeinse nominatie veroverde met een rigide rechts programma, maar niet iemand die de democratische rechtstaat of het politieke systeem omver wilde werpen of daaraan heeft bijgedragen. Hij verlegde enkel het debat – geen kleinigheid maar geen sabotage van de Amerikaanse republiek. Een analyse van Amerikaanse conservatisme en waarom dat zo bepaalde richtingen in gaat, zou De Foers volgende boek moeten zijn. Dan kan ook iemand als William Buckley, veel belangrijker voor Amerikaans conservatisme dan Lindbergh en McCarthy, aan bod komen.

De oervader

Naar mijn idee begint de teloorgang van Amerika met Richard Nixon, althans met zijn presidentschap. Alles wat er fout is met Amerika in 2024 vindt zijn oorsprong bij deze man, is mijn boude stellingname. Nixon is de oervader van het huidige Amerika.

De Foer schrijft korte bio’s van uiteindelijk veertien Republikeinen, of beter gezegd, uiterst rechtse Amerikanen. Pat Buchanan, een voormalig speechwriter van Nixon die in de jaren negentig de eerste radicaal rechtse presidentskandidaat werd, kreeg op de conventie van 1992 van de oude Bush alle ruimte voor zijn cultuuroorlog boodschap. De eerste man die ermee scoorde, maar hij zou het voorlopig buiten de Republikeinse Partij doen, als tweevoudig presidentskandidaat – zonder succes, overigens.

Na Gingrich, een man die ik de vernietiging van Amerikaanse normen meer kwalijk neem dan Trump (Trump doet wat hij doet, Gingrich had een vooropgezet plan voor die vernietiging en voerde het bekwaam uit), schuift De Foer Karl Rove (de politieke tovenaar van kleine Bush), Sarah Palin (de domme gans uit Alaska), Mitch McConnell, het Supreme Court, Marjory Taylor Greene, Mike Johnson en Donald Trump naar voren. Mike Johnson moet een late toevoeging zijn geweest, de afgevaardigde uit Louisiana kenden we een jaar geleden nog niet. Hij werd Speaker toen Kevin McCarthy (die in De Foers verhaal als opportunist en Trump fluisteraar een belangrijkere rol zou moeten spelen) werd afgezet. Mike Johnson kan bezwaarlijk beschouwd worden als een wegbereider van de teloorgang van de GOP, ook al is hij een maffe geloofsgekke zuiderling. En waarom niet onappetijtelijke opportunisten als Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio en andere hielenlikkers van de psycho uit Florida.

Met alle respect, de tweede helft van de door De Foer geschetste lui zijn, afgezien van McConnell en Trump, kleine krabbelaars in dit destructieve spectrum, zoals ook Rush Limbaugh, de haatpraat radiotoeter, dat was. Nog afgezien van de in een aantal gevallen niet erg interessante bio’s van deze lieden, overdrijft De Foer hun belang. Ze zijn eerder de uitkomst van de destructieve keer van de Republikeinen dan de oorzaak. Het wordt dan ook arbitrair, want waar is kleine Bush en waar is Dick Cheney, de vicepresident die een oorlog veroorzaakte met zijn leugens en het politieke systeem fundamenteel ondermijnde? En ik zou zelf ook aandacht besteed hebben aan meezwemmende (nou ja, spartelende) Republikeinen als John McCain en Mitt Romney. Dat waren keurige lieden die door hun bereidheid normen te laten varen om nominaties te verwerven (en in McCains geval de Sarah Palins van deze wereld een platform te geven) de in gang gezette ontwikkelingen niet bekritiseerden, laat staan stopten. McCain en Romney plaveiden op hun eigen manier de weg voor Trump.

Vergeet de Democraten niet

Een beperking van De Foers boek is ook dat door zijn focus op de Republikeinse Partij de bijdragen van de Democraten aan de teloorgang van Amerika onderbelicht blijft. De stupide progressieve kritiek op Ronald Reagan, de afwijzing met verkeerde argumenten van rechter Bork voor het Supreme Court, de besmeuring van het presidentschap door Bill Clinton en de demonisering van kleine Bush droegen er het hunne aan bij. Ik verwijt Hillary Clinton nog steeds dat ze in 2016 als te oud, has been, per se kandidaat wilde zijn en zo Trump aan de macht hielp. En dit jaar doet de bejaarde ijdeltuit Joe Biden hetzelfde.

Een boek over het afglijden van Amerika is interessanter dan enkel vertellen waarom de Republikeinen zo intens slecht zijn, verwerpelijke sekte van Trump-volgelingen als die partij ook is geworden. En uiteindelijk is het lezen van deze veertien bio’s het consumeren van veertien verhalen over vaak heel vervelende en soms totaal oninteressante mensen (Taylor Greene). Vandaar dat moest denken aan Groenhuijsens observatie over het lezen van boeken over vervelende lui.

De Foer heeft gegeven zijn uitgangsstelling een adequaat boek geschreven maar helaas krabt hij hoogstens aan de oppervlakte van hoe Amerika naar de filistijnen gaat en wie daarvoor verantwoordelijk is/zijn. Dat zijn helaas niet enkel de Republikeinen.

De saboteurs is een gemakkelijk leesbaar boek dat meer vragen oproept dan beantwoordt.